Many people are fascinated by the Tudor era and have a real thirst for uncovering what really happened. Sometimes it’s hard to find the time, especially to dig a little deeper and go beyond the standard history books, novels and TV series. As this is the case, I thought it might be useful to share some thoughts from my own research, focusing on easily accessible resources and a few of my favourites.

This is one of a series of blogs to allow you to pick and choose between the aspects which most interest you.

- This blog explores resources for researching the wider national and religious tensions of the Tudor period, particularly during the reign of Elizabeth I.

- The second blog examines researching the impact these had on the city of York in the North of England and the grand and not so grand people who lived there.

- The third blog will focus on researching the history of one remarkable woman who lived in Elizabethan York, Margaret Clitherow.

The basic history of the religious changes in England during the Tudor period is well known. Henry VIII broke away from the Catholic Church in Rome, to achieve a divorce from Catherine of Aragon (by stating the marriage had never been valid) so he could marry Anne Boleyn. Thomas Cromwell led the dissolution of the monasteries to raise money for Henry, although perhaps the subsequent closer of the smaller chantries is even more interesting.

Cromwell attempted to subtly move the Church of England towards a more Protestant direction. This was accelerated under Henry’s Protestant son Edward VI, but quickly reversed under the rule of “Bloody” Queen Mary I, who led a reconciliation with Rome.

When Mary died, Elizabeth I moved the Church of England back in a Protestant direction. The religious divide hardened, especially following 1570 when the Pope excommunicated Elizabeth by issuing a Papal Bull, giving absolution to Catholics who wanted to remove her.

All the above took place in less than forty years. It’s bewildering to read, research and write about. What must it have been like to live through? Under Mary, you could be burned for being a Protestant heretic. Before and after her reign, it was illegal not to attend the Protestant Church. Later, under, Elizabeth you could be executed for even giving a drink to a Catholic priest.

Fascinating though this is, you can find out about it in basic history books. If you want to delve a little deeper, where should you look?

One of the most fascinating resources I uncovered was a set of volumes called “The Statutes at Large from Magna Carta to The Union of the Kingdoms of Great Britain and Ireland”. Versions of these can easily be found online. You can download digital scanned copies and/or purchase paper-based formats.

For example, Volume IV details every law introduced between 1553 under Mary I to 1640 under Charles I. The volume provides fascinating insights into government thinking at the time.

Right at the start of Volume IV, we see the first laws enacted under Mary, including “An Act declaring the Queen’s Highness to have been born in a most just and lawful matrimony, and also repealing all Acts of Parliament and sentences of Divorce, had and made to the contrary”. Mary was quick to right the wrongs she considered had been made by her father Henry VIII, when he’d divorced her mother Catherine of Aragon.

Equally, Mary wanted to reinstate the Catholic Church and remove many of the laws introduced by her Protestant half brother Edward. The act above is quickly followed by the “Act for the Repeal of certain Statutes made in the Time of the Reign of King Edward the Sixth”.

Looking at the start of Volume IV in PDF format, it might be easy to think this document is simply a long list of laws, but the content is much more than that. If you scroll past the page listing the acts, you’ll find clause by clause and paragraph by paragraph entries for every single act. Some of these are eye opening.

If we move to Elizabeth I’s time, it’s fascinating to see how she reacted to the Papal Bull of 1570. The next Parliament passed a new Treason Act. This laid down that even speaking maliciously about the Queen was high treason.

Here’s an extract from Volume IV of The Statues at Large:

“…by writing, printing, preaching, speech, express words, or sayings maliciously, advisedly, and directly publish, set forth, and affirm that… our said sovereign lady, Queen Elizabeth, is a heretic, schismatic, tyrant, infidel, or an usurper of the crown of the said realms or any of them; that then all and every such said offence or offences shall be taken, deemed, and declared, by the authority of this act and parliament, to be high treason.”

There are so many examples from the Statutes which make fascinating reading (and, of course, some which don’t!), but we should move on to cover other resources.

One of the really good ones is the British History Online website. The Journal of the House of Lords entries on the website, for example, offers some fantastic insights.

At the opening of Elizabeth’s first Parliament, William Cecil’s brother-in-law, Nicholas Bacon, was appointed Lord Keeper of the Great Seal. The Journal describes how he made the following declaration on the Queen’s behalf:

“Now the Matters and causes whereupon you are to Consult, are chiefly and principally three points. Of those the first is of well making of Laws, for the according, and uniting of these people of the Realm into a uniform order of Religion, to the Honour and Glory of God, the establishing of the Church, and Tranquillity of the Realm. The second, for the Reforming and removing of all Enormities, and Mischiefs, that might hurt or hinder the Civil Orders and Policies of this Realm. The third and last is, advisedly and deeply to weigh and consider the Estate and Condition of this Realm, and the Losses and Decays that have happened of late to the Imperial Crown thereof; and therefore to advise the best remedies to supply and relieve the same.”

Elizabeth’s and so Parliament’s priorities were clear – uniformity of religion (in a Protestant rather than Catholic Church), law and order and the economy. It doesn’t sound too far off from what might happen in a modern day Westminster!

A third great resource is the online Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. This provides access to 60,000 biographies of the people who’ve shaped British history. Admittedly, there’s a question about subscription access to some of the content here. I’m lucky. Due to my role at a UK university, I have free access. The good news is that many other people in the UK can also have free access – as long as you’re a member of a library. For others, there are options for paid subscriptions. It’s a great resource but as there’s not universal access, I won’t focus too much time on it here.

The last resource I thought I’d mention is one you definitely have – if you’re reading this blog – access to a web browser and a search engine. As I tell my students, the search engine is your friend… but don’t just look at the obvious places. Having said that, Wikipedia can be useful, especially if you go to the bottom and use the list of references.

Searching the wider web I’ve found many fabulous and freely publicly available resources, including books, articles, websites, PhD research dissertations and other things. For example, I found a great article which was both relevant and useful for my own writing, as it focused on the disguises used by Catholic priests in Tudor and Stuart England.

There are of course, many other sources. I’ve been lucky in my own research (despite the pandemic) to be helped by some great people in local libraries and universities and at special places, such as the York Minster Library Collections team. I’d love to know something about your own favourite resources and tips for researching Tudor history.

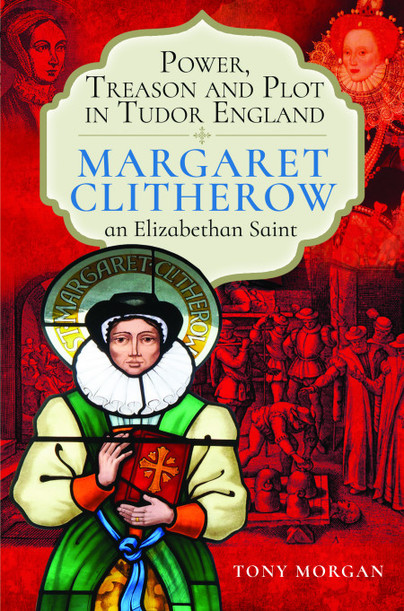

By now, you might be wondering why I was doing this research? As well as writing three historical novels (including The Pearl of York), I’ve just had my first non-fiction history book published. If you like researching Tudor history, you might like it just for the biography!

Power, Treason and Plot in Tudor England looks at national power and religious struggles, the impact they had on the city of York and the life and death of one woman, Margaret Clitherow. The book is available from the publisher Pen and Sword’s website, Amazon and at many good book shops.

If you found this article interesting, please return soon, as I’ll be posting links to the follow-on blogs about researching Tudor York and Margaret Clitherow.

One thought on “Researching the Tudor Period”